Fridtjof Nansen i jego wyprawy polarne 1888 – 1896. Część I.

Pierwsza wyprawa na nartach przez Grenlandię 1888-1889

Moja wizyta w Fram Museum jesienią 2022 tak bardzo mi się podobała, że kolejne odwiedziny w tym przybytku były tylko kwestią czasu. A że zimą jakiekolwiek wędrówki po górach są mocno ograniczone, to postanowiłem poświęcić jeden lutowy dzień na powrót w świat wypraw polarnych przełomu XIX i XX wieku.

Relacjonując tę wycieczkę, mógłbym w zasadzie napisać dokładnie to samo co wcześniej. Tamten wpis jest tutaj. Niewiele zmian zauważyłem w stosunku do poprzedniego razu. Wobec tego postaram się przybliżyć nieco szerzej wyczyny jednego z największych norweskich bohaterów narodowych, Fridtjofa Nansena. Z góry jednak uprzedzam, że będzie to jedynie pobieżny skrót jego życiorysu i najważniejszych dokonań.

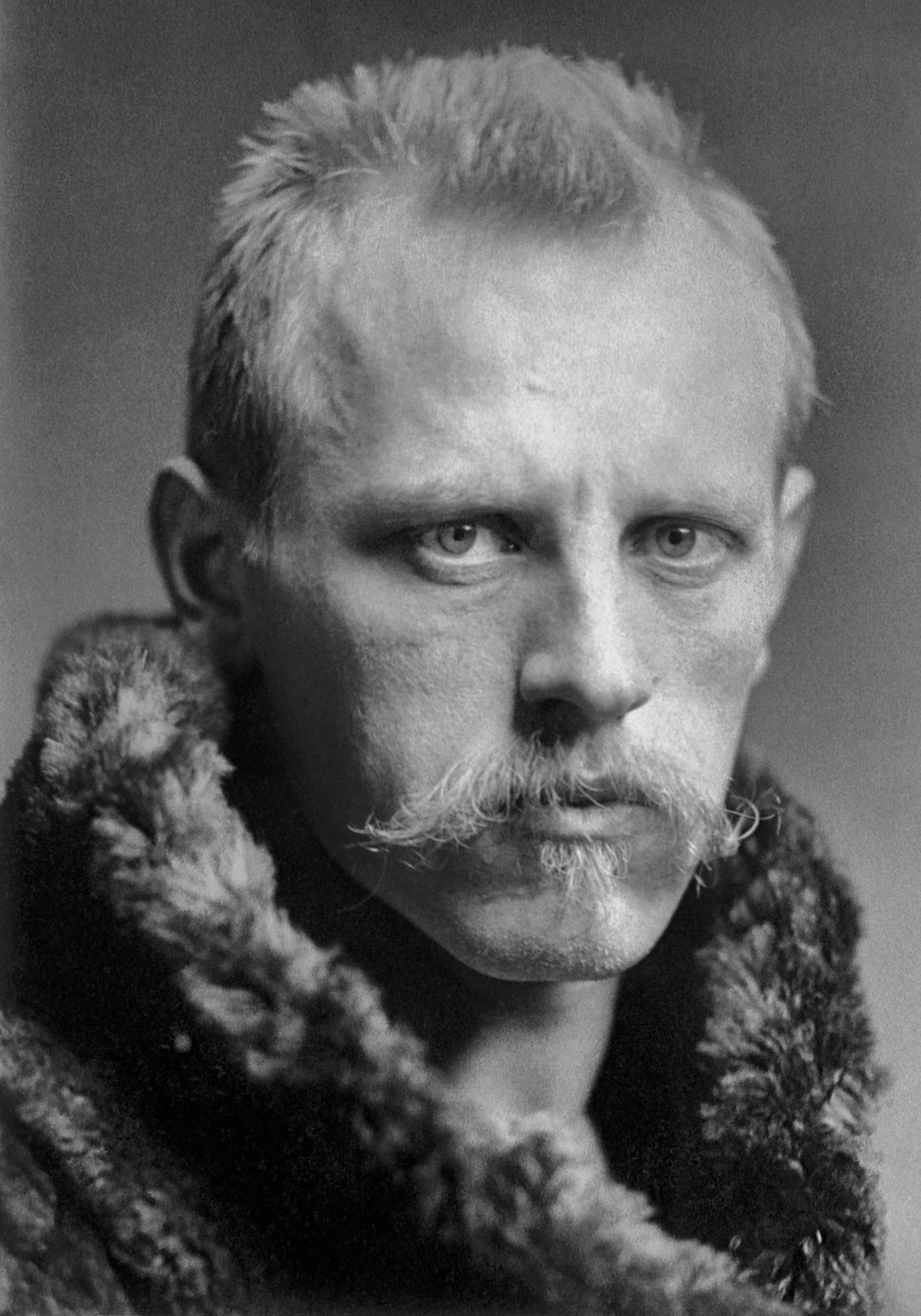

Fridtfjof Nansen (1861-1930) był prawdziwym człowiekiem renesansu, z rozległym polem zainteresowań i osiągnięć. Był pionierem narciarstwa rekreacyjnego oraz naukowcem specjalizującym się w kilku dziedzinach. Studiował biologię na Uniwersytecie w Chistianii (ówczesnym Oslo), a także brał udział w wyprawie naukowej na Grenlandii (1882), gdzie badał tamtejsze populacje fok. Już wówczas zainteresował się niezbadanym wówczas lądem.

W 1888 roku wraz z piątką innych śmiałków wybrał się ponownie na Grenlandię aby przejść ją pieszo ze wschodu na zachód. Oprócz typowo sportowej ambicji, chciał przekonać się i udokumentować jak wygląda wnętrze kontynentu, które w tamtym czasie było jedynie białą plamą na mapie. Nansen zamierzał rozpocząć wędrówkę od niezamieszkanego wschodniego wybrzeża, co było posunięciem ryzykownym i spotkało się z ostrą krytyką wśród ekspertów. Większość początkowo określiła plan jako dzieło szaleńca. Uznano za niemożliwe, aby narciarz bez psów i sań mógł pokonać śródlądowy lód, a brak bazy w sytuacji awaryjnej uznano za nieodpowiedzialny. Jego podejście „zachodnie wybrzeże albo śmierć” (The west coast or death) zakładało tylko jeden kierunek marszu i wykluczało jakikolwiek odwrót. Jak sam pisał po latach: „Zawsze myślałem, że tak chwalona linia odwrotu jest pułapką dla ludzi, którzy chcą osiągnąć swój cel”.

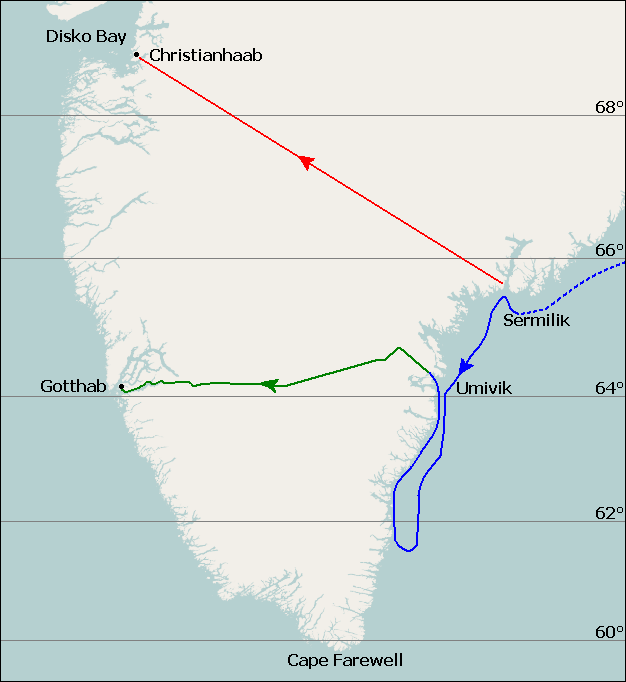

Za punkt wyjścia obrano obszar wokół fiordu Sermilik, na zachód od Angmagssalik (65°35’ N), które było najbardziej na północ wysuniętą osadą Eskimosów we wschodniej Grenlandii. Celem natomiast miał być Christianshåb w Disco Bay na zachodnim wybrzeżu. Tam też zawijały statki wielorybnicze z Europy, co było ich biletem powrotnym do domu. Cała trasa liczyła około 600km w linii prostej. Duński kupiec Augustin Gamél zgodził się sfinansować wyprawę Nansena, kiedy okazało się, że nie otrzyma on dotacji z Uniwersytetu (wyprawa miała mieć charakter naukowy).

Ścisły umysł i naukowe podejście do ekspedycji sprawiły, że plan był przygotowywany w najdrobniejszych szczegółach. Sprzęt i prowiant były sprawdzane niezwykle skrupulatnie. Odzież, narty, sprzęt kuchenny, namiot i żywność zostały przetestowane i zmodyfikowane aby spełniały wyśrubowane wymagania Nansena.

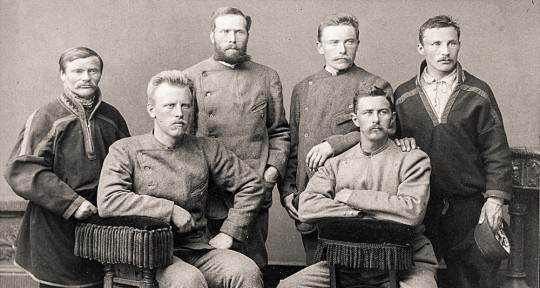

Oprócz samego Nansena, do udziału w wyprawie zostało wyselekcjonowanych pięciu mężczyzn: Oluf Christian Dietrichson (żołnierz, biegły w posługiwaniu się bronią), Ole Nilsen Ravna (z norweskiej społeczności samów, doświadczony narciarz), Otto Neumann Knoph Sverdrup (farmer, myśliwy i żeglarz, późniejszy uczestnik kolejnej wyprawy Nansena na statku Fram), Kristian Kristiansen (drwal), Samuel Johannesen Balto (z norweskiej społeczności samów, doświadczony narciarz).

Szóstka śmiałków dotarła na Grenlandię 4 czerwca 1888 r. na statku do połowu fok. Z uwagi na dryfujący lód wzdłuż wybrzeża, nie mogli dostać się na ląd. Po dwóch tygodniach poszukiwań dogodnego miejsca do lądowania, postanowiono popłynąć przez wąskie cieśniny w lodzie na dwóch łodziach. Zadanie okazało się o wiele trudniejsze niż początkowo zakładali. Silny prąd i dryfujące kry groziły zmiażdżeniem łodzi i trzeba było je wyciągać na lód i spędzić na nim noc. Następny dzień okazał się jeszcze mniej udany. Poranek zastał ich w znacznej odległości od lądu, a wkrótce prąd morski poniósł ich dalej na południe. Fale przybrały na sile i zaczęły rozbijać krę lodową, na której dryfowali. Mężczyźni przedostali się jakoś na inny, większy kawałek lodu, ale ich sytuacja wydawała się dramatyczna. Nawet kiedy znów ujrzeli słońce i pogoda zaczęła się poprawiać, prąd znosił ich coraz bardziej na południe. Ścierające się ze sobą kry lodowe groziły zniszczeniem ich niewielkiego obozowiska w każdej chwili i wrzuceniem ich do lodowatego oceanu. Pomimo organizowania wacht by być w gotowości na natychmiastowe wodowanie łodzi, niewiele mogli zrobić. Po kilku dniach dryfu lód przerzedził się i mogli wsiąść z powrotem do łodzi.

Powiosłowali do niewielkiej zatoczki, gdzie mogli wreszcie zejść na ląd i odpocząć. Okazało się, że prąd zniósł ich 380 km od planowanego miejsca lądowania i teraz musieli dotrzeć z powrotem na północ, do miejsca, gdzie zamierzali zacząć wędrówkę przez kontynent. Trasę tę pokonywali głównie w łodziach, wiosłując wzdłuż brzegu. Ostatecznie ich plan został zmodyfikowany z uwagi na dotychczasowe trudności, a także po wstępnych rekonesansach wgłąb Grenlandii i sprawdzeniu jak prezentuje się rzeźba terenu.

Wyruszyli 15 sierpnia, ciągnąc pięć sań z ekwipunkiem i zapasami jedzenia. Poruszali się na nartach lub rakietach śnieżnych, przechodząc przez lodowiec i wspinając się po niezbadanych wcześniej grenlandzkich górach. Przez kilka pierwszych dni sprzyjała im pogoda, potem musieli zmagać się z przeciwnym wiatrem i i opadami śniegu. W którymś momencie spięli sanie razem, skonstruowali maszt i wciągnęli na niego żagiel. Chcieli zdążyć na zachodnie wybrzeże zanim sezon żeglugowy się zakończy i móc wrócić bezpiecznie do cywilizacji. Do celu wciąż jednak było daleko. Pierwotny plan ponownie zmieniono i udali się w kierunku osady Godthaab (dzisiejsze Nuuk), położonej bardziej na południe. Ich dystans do przejścia miał się dzięki temu zmniejszyć o około 150 km. Temperatury za dnia wahały się pomiędzy -15 a -20 stopni, nocą zaś spadały poniżej -40 stopni Celsjusza. Zmagali się wiec nie tylko z głodem, pragnieniem i zmęczeniem, ale również z brakiem ciepła.

4 września minęli najwyższy szczyt, liczący 2720m n.p.m. i zaczęli sukcesywnie schodzić. Żaglowanie saniami po śniegu i lodzie było o tyle ryzykowne, że w każdej chwili mogli wpaść szczelinę lodową ale na szczęście udało im się tego uniknąć. W końcu dotarli do granicy lodu i odtąd mogli iść już po stałym gruncie.

26 września wreszcie stanęli na brzegu fiordu Ameralik. Aby dotrzeć do cywilizacji, zbudowali dwuosobową, prymitywną łódź, wykorzystując elementy sań i wyposażenia oraz gałęzie rosnących w okolicy wierzb i olch. Nansen wraz z Sverdrupem wyruszyli w niej 29 września i dotarli do Godthaab cztery dni później, żywiąc się upolowanymi mewami. Na miejscu dowiedzieli się, że ostatni statek, którym mogliby wrócić do Europy odpłynął jeszcze zanim rozpoczęli swoją wędrówkę przez kontynent. Jedyna dostępna jednostka znajdowała się 500 km dalej i wkrótce ona także miała opuścić Arktykę. Miejscowi Eskimosi pomogli Nansenowi sprowadzić do Godthaab pozostałych członków ekspedycji, a także przekazać wiadomość o sytuacji grupy do kapitana wspomnianego statku. Ten odpowiedział mu, że nie może już dłużej czekać z wypłynięciem, ale obiecał przekazać jego listy do Skandynawii.

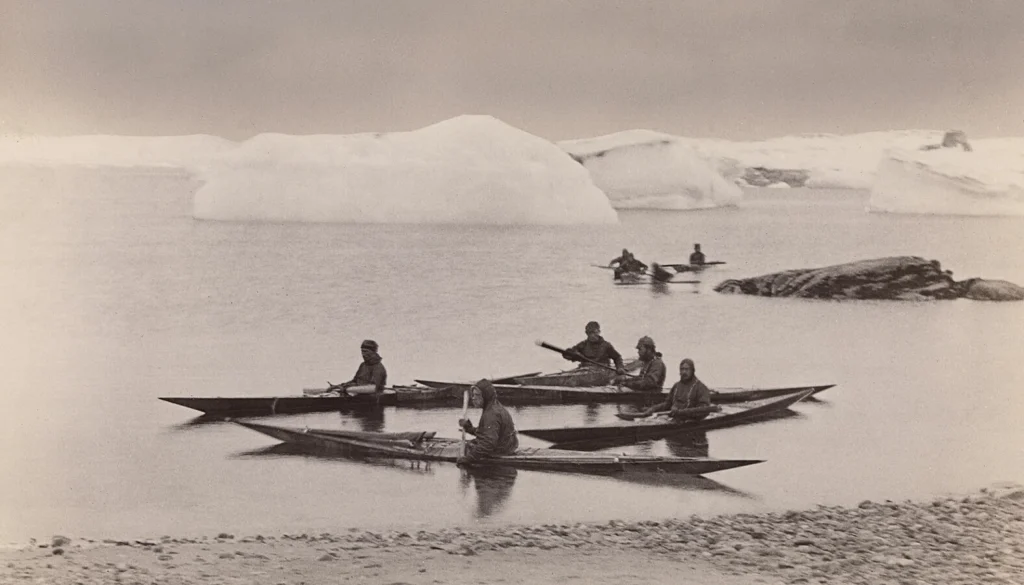

Wyglądało na to, że Norwegowie będą musieli spędzić całą zimę w Godthaab w towarzystwie Innuitów oraz duńskich Grenlandczyków. Naukowa natura Nansena pomogła mu wykorzystać ten czas na studiowanie zwyczajów rdzennych mieszkańców i ich sposobów przetrwania w arktycznych warunkach. Norwegowie podpatrywali, jak miejscowi się ubierają, w jaki sposób polują czy jak konstruują tradycyjne kajaki. Po powrocie do kraju, Nansen opublikował książkę o swoich badaniach w Godthaab, „Życie Eskimosów” (Eskimoliv, 1891), gdzie żywo opisał swoją miłość do Grenlandii i jej mieszkańców. Tak między innymi opisywał swoje wrażenia z pobytu w społeczności Innuitów: „Badaliśmy styl życia Eskimosów, próbowaliśmy nauczyć się wiosłować kajakiem i polować. Są to niezwykle nieskażeni i czarujący ludzie natury, o prostych stosunkach społecznych i sposobie życia, gdzie zazdrość, chciwość i różnice klasowe nie spowodowały, że ludzie stali się chciwi i zazdrośni.” Nansen szkicował, fotografował i polował, doświadczając w pełni prostego, prymitywnego życia, które kochał. W swoich książkach z niekłamaną radością opowiada o niektórych z tych wypraw łowieckich – z dala od zmartwień cywilizacji i otoczony poczuciem całkowitej wolności.

Kolekcję przedmiotów codziennego użytku, zebraną wówczas przez Nansena można dziś oglądać w Muzeum Fram.

Pod koniec kwietnia 1889 r. do osady zawinął pierwszy statek (Hvidbjørnen), którym cała norweska ekspedycja mogła powócić, najpierw do Kopenhagi, a następnie do Christianii (Oslo). Tam powitały ich wiwatujące tłumy. Nansen z miejsca stał się bohaterem narodowym, ale jego największe osiągnięcie miało dopiero nadejść w kolejnych latach.

Pionierskie przejście na nartach przez Grenlandię to wyczyn niezwykły. Nawet w obecnych czasach, pokonanie tego surowego kontynentu w poprzek, zdając się na kapryśną pogodę i własne umiejętności to nie lada wyczyn. Nansen pozbawiony był takich nowinek technicznych jak gps, radio, łączność satelitarna. Nie miał żadnej bazy wypadowej, do której mógłby zawrócić w razie niepowodzenia. Podczas przejścia przez lodowiec, groziły jego ekipie liczne szczeliny w lodzie, wszyscy cierpieli głód z powodu skromnych racji żywnościowych, na niedobór tłuszczu, a także pragnienie, gdyż jedyną wodę jaką mogli pozyskać była ta z roztopionego śniegu. Temperatury spadały do minus 45 stopni a wiatr i śnieżyce nie ułatwiały im życia. Ich podróż przez lodowe pustkowie zajęła sześć tygodni, podczas których pokonali 450 km, zapisując się na trwałe w historii.

I enjoyed my visit to the Fram Museum in the fall of 2022 so much that my next visit to this place was only a matter of time. And since in winter any hiking in the mountains is very limited, I decided to devote one February day to returning to the world of polar expeditions of the 19th and 20th centuries.

When reporting on this trip, I could basically write exactly the same thing as before. That entry is here. I didn’t notice so much changes compared to last time. Therefore, I will try to explain in more detail one of the greatest Norwegian national heroes, Fridtjof Nansen. However, I warn you in advance that this will only be a brief summary of his biography and his most important achievements.

Fridtfjof Nansen (1861-1930) was a true Renaissance man, with a wide field of interests and achievements. He was a pioneer of recreational skiing and a scientist specializing in several fields. He studied biology at the University of Chistiania (then Oslo), and also took part in a scientific expedition to Greenland (1882), where he studied the local seal populations. Already then he became interested in the unexplored land.

In 1888, together with five other adventurers, he went to Greenland again to cross it on foot from east to west. In addition to his typical sporting ambition, he wanted to see and document what the interior of the continent looked like, which at that time was just a blank spot on the map. Nansen intended to start his trek from the uninhabited eastern coast, a risky move that drew heavy criticism from experts. Most initially described the plan as the idea of a madman. It was considered impossible for a skier without dogs and sleds to cross the inland ice, and the lack of a base in an emergency situation was considered irresponsible. His motto „west coast or death” approach assumed only one direction of march and excluded any retreat. Nansen wrote years later: „I always thought that the much-praised line of retreat was a trap for people who wanted to achieve their goal.”

The starting point was the area around Sermilik Fjord, west of Angmagssalik (65°35′ N), which was the northernmost Inuit settlement in eastern Greenland. The destination was to be Christianshåb in Disco Bay on the west coast. Whaling ships from Europe also stopped there, which was their ticket back home. The entire route was approximately 600 km in a straight line. The Danish merchant Augustin Gamél agreed to finance Nansen’s expedition when it turned out that he would not receive a subsidy from the University (the expedition was supposed to be of a scientific nature).

A precise mind and a scientific approach to the expedition meant that the plan was prepared down to the smallest detail. Equipment and provisions were checked extremely carefully. Clothing, skis, kitchen equipment, tent and food were tested and modified to meet Nansen’s exacting requirements.

In addition to Nansen, five men were selected to participate in the expedition: Oluf Christian Dietrichson (soldier, skilled in using weapons), Ole Nilsen Ravna (from the Norwegian Sami community, experienced skier), Otto Neumann Knoph Sverdrup (farmer, hunter and sailor, participant of Nansen’s next expedition on Fram), Kristian Kristiansen (lumberjack), Samuel Johannesen Balto (from the Norwegian Sámi community, an experienced skier).

The six brave men reached Greenland on June 4, 1888, on a seal fishing vessel. Due to the drifting ice along the coast, they could not get to land. After two weeks of searching for a suitable landing place, it was decided to sail through the narrow straits in the ice on two boats. The task turned out to be much more difficult than they initially expected. The strong current and drifting ice floes threatened to crush the boats and they had to be hauled onto the ice and spend the night there. The next day turned out to be even less successful. The morning found them a good distance from land, and soon the sea current carried them further south. The waves became stronger and began to break the ice floe on which they were drifting. The men somehow managed to go on another, larger piece of ice, but their situation seemed dramatic. Even as they saw the sun again and the weather began to improve, the sea current carried them further and further south. Clashing ice floes threatened to destroy their small camp at any moment and throw them into the icy ocean. Despite organizing watches to be ready for an immediate boat launch, there was little they could do. After a few days of drifting, the ice thinned out and they were able to get back into the boats.

They paddled to a small bay where they could finally disembark and rest. It turned out that the current had carried them 380 km from the planned landing site and now they had to get back north to the place where they intended to start their trek across the continent. They traveled this route mainly in boats, rowing along the shore. Ultimately, their plan was modified due to the current difficulties, as well as after preliminary reconnaissance deep into Greenland and checking the relief of the terrain.

They set off on August 15, pulling five sleighs with equipment and food supplies. They moved on skis or snowshoes, crossing the glacier and climbing previously unexplored Greenlandic mountains. The weather was favorable for the first few days, but then they had to deal with contrary winds and snowfall. At some point they fastened the sleigh together, constructed a mast and hoisted a sail onto it. They wanted to make it to the west coast before the shipping season ended so they could return safely to civilization. However, it was still far from the goal. The original plan was changed again and they headed towards the settlement of Godthaab (present-day Nuuk), further south. Their crossing distance was to be reduced by approximately 150 km. Temperatures during the day ranged between -15 and -20 degrees, and at night it dropped even below -40 degrees Celsius. So they struggled not only with hunger, thirst and fatigue, but also with the lack of warmth.

On September 4, they passed the highest peak, 2,720 m above sea level. and they started to descend gradually. Sailing the sleigh on snow and ice was risky because they could have fallen into an ice crevice at any moment, but fortunately they managed to avoid it. Finally they reached the edge of the ice and from that moment, they could walk on solid ground.

On September 26, they finally reached the shore of Ameralik Fjord. To reach civilization, they built a two-person, primitive boat, using elements of sleds and equipment, as well as branches of willows and alders growing in the area. Nansen and Sverdrup set off on September 29 and reached Godthaab four days later, feeding on hunted seagulls. Once there, they learned that the last ship that would take them back to Europe had sailed away before they started their journey across the continent. The only available vessel was 500 km away and soon she too would leave the Arctic. The local Eskimos helped Nansen bring the remaining members of the expedition to Godthaab, as well as convey news of the group’s situation to the captain of the ship in question. He replied that he can not wait any longer to sail, but promised to deliver his letters to Scandinavia.

It seemed that the Norwegians would have to spend the entire winter in Godthaab in the company of the Innuit and Danish Greenlanders. Nansen’s scientific nature helped him use this time to study the customs of the indigenous people and their methods of survival in Arctic conditions. The Norwegians observed how the locals dressed, how they hunted and how they constructed traditional kayaks. After returning home, Nansen published a book about his research in Godthaab, The Life of the Eskimos (Eskimoliv, 1891), where he vividly described his love for Greenland and its people. This is how he described his impressions of his stay in the Innuit community: 'We studied the Eskimo lifestyle, tried to learn how to row a kayak and hunt. They are an extremely pure and charming people of nature, with simple social relations and a way of life, where jealousy, greed and class differences have not caused people to become greedy and jealous.” Nansen sketched, photographed, and hunted, fully experiencing the simple, primitive life he loved. In his books, he talks with genuine joy about some of these hunting expeditions – away from the worries of civilization and surrounded by a sense of complete freedom.

The collection of everyday objects collected by Nansen can be seen today in the Fram Museum.

At the end of April 1889, the first ship (Hvidbjørnen) arrived to the settlement, and the entire Norwegian expedition could return, first to Copenhagen and then to Cristiania (Oslo). There they were greeted by cheering crowds. Nansen instantly became a national hero, but his greatest achievement was to come in the following years.

Pioneering a ski crossing through Greenland is an extraordinary feat. Even in today’s times, crossing this harsh continent across, relying on the capricious weather and your own skills, is no small feat. Nansen was deprived of such technical innovations as GPS, radio, and satellite communications. He had no base to return to in case of failure. While crossing the glacier, his team was threatened by numerous crevices in the ice, everyone suffered from hunger due to meager food rations, lack of fat, and thirst, because the only water they could get was from melted snow. Temperatures dropped to minus 45 degrees and wind and blizzards did not make their lives easier. Their journey through the icy wasteland took six weeks, during which they covered 450 km, making a permanent mark in history.